Nat Young's Contact High

Drew Kampion interviews the legendary surfer and cannabis advocate

Editor's note: In 2007, surf writer Drew Kampion interviewed World Champion surfing icon Nat Young for The Skate/Surf Issue of Heads Magazine. Their discussion centred on cannabis’ influence on professional sports. Never one to shy away from controversy, Nat was very forthcoming on the role pot played in shaping him as a surfer and a human being. Today, as more professional athletes step forward in support of cannabis as an integral part of competitive sports, let us revisit the wisdom of surf’s tribal elder. Nat Young was ahead of his time and helped lay the groundwork for athletes to come clean about their cannabis consumption.

***

An acquired skill of most prominent sports figures is to offer up safe generalities and pleasant sound bites in response to the media’s probing questions. The idea is to avoid controversy and maintain a veil of professionalism. But Australian surfer Nat Young has taken a different tack. Over the 40 years since he won the World Surfing Contest in San Diego (1966), he has produced a series of films, books, and interviews, offering up a hefty body of exposition on what it’s like to be Nat Young along with an expansive elucidation on the world of sport, politics, and culture.

As World Champion, he parlayed his notoriety into icon status. He was a dominating surfer, a columnist for the Sydney Sunday Telegraph, and a key player in the late-60s “shortboard revolution,” which was a period of profound change in surfing that saw surfboard drop from nine and ten feet long to six and seven—opening the door to greater freedom and manoeuvrability. Nat featured prominently in several important surf movies of the day and continued to compete until, in the early 1970s, he dropped out to join a back-to-the-land group on Australia’s north-central coast, where he surfed in relative isolation and contemplated his place in the universe.

A candid proponent of the judicious use of marijuana, he seemed to repudiate the competition scene for the most part, convinced that surfing was an art form and more—a religion—and that the worldwide community of surfers is tantamount to a tribe. He felt that members of the tribe should know the history of their sport and its culture, so he researched, gathered photos, and wrote the first truly comprehensive and informed History of Surfing. He also wrote instructional books and produced a film on the similarities of gravity sports (The Fall-Line). He returned to Sydney (where he was born) later in the 70s and ran for the New South Wales State Parliament in 1986 on an environmental platform. Capturing 47 percent of the vote, he was able to leverage his influence into new clean-water legislation. Despite a serious spinal injury, he returned to competition in the late 1980s to become a four-time World Longboarding Champion. In the years since, he has pursued a rigorous work and travel schedule, while surfing on water or snow virtually every day of his life.

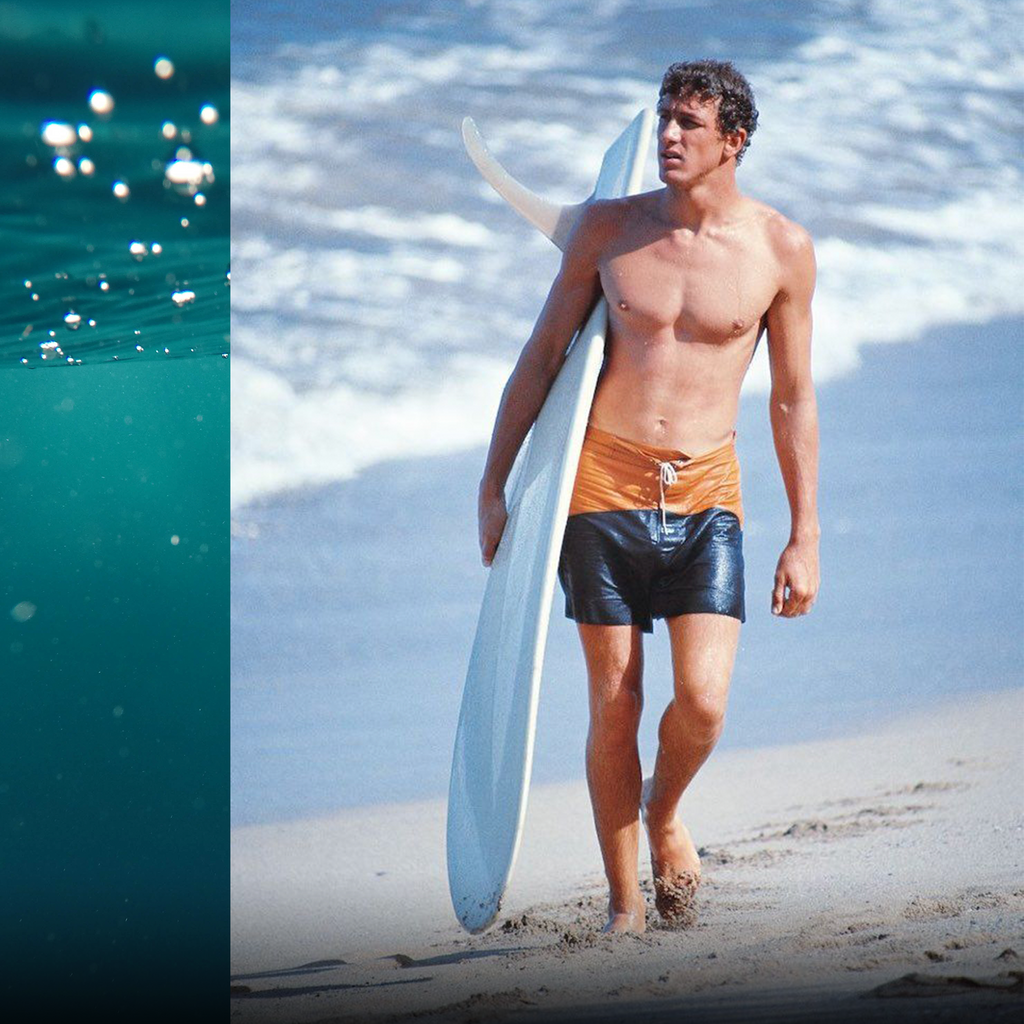

In the late 60s, Nat Young was part of an influential group of surfers who pushed to boundaries of surfing and surfboard design.

The quintessential renaissance surfer, Nat is equally at home grovelling on some remote beach or choosing from the wine list in Biarritz, France. His average day is as full as an average man’s week. Surfing remains the centrepiece of what he calls “a beautiful life.” Indeed, Young, the self-styled icon and tribal elder, the author, publisher, filmmaker, teacher, lobbyist, fashion model, businessman, spokesperson, pilot, gourmand, instigator, theorist, philosopher (surfers do sometimes get wise), surfboard shaper, politician, adventurer, and skilled practitioner of surfing and other gravitational gratifications including skiing, snowboarding, river rafting, and windsurfing, is as much a man of the mind as he is a man of the body. His ongoing war, for over four decades now, has been with bullshit, a commodity with which he himself has occasionally been associated. His chief weapon (and general conversational style) has been brutal honesty, admittedly from his own subjective point of view.

Assertive by nature, Young has had his conflicts over the years, but he has always found a way to profit and learn from his experiences. In March of 2000, when he was beaten to a pulp by another surfer at his local spot at Angourie in New South Wales, Nat’s swollen, unrecognizable mug—a portrait in vivid purples and oranges—appeared on the front pages of newspapers around the world. It took hours of reconstructive surgery and plenty of titanium mesh to pull his face back together, but by the time he was out of the hospital, he was already well along on a new book of essays, titled Surf Rage, which brought the issue of sport and violence to centre stage in the surfing world.

Nat Young defined the role of a tribal elder, and he lives it to the hilt.

Few in surfing (or any other endeavour, for that matter) have so thoroughly and diligently pondered their purpose as Young. And no one in surfing has taken on the mantle of educator, inspirer, enlightener, and leader the way he has. He’s defined the role of a tribal elder, and he lives it to the hilt.

Married with four children (one of them, Beau, is also a champion surfer) and currently updating The History of Surfing for a new edition (Gibbs Smith, Publisher), Nat lives in Australia for much of the year, but returns to his condo in Sun Valley, Idaho for the winter snow. That’s where I caught up with him in February of this year.

Nat "The Animal" Young redefined what could be done on the face of a wave largely due to an open-minded attitude inspired by his cannabis use.

Drew Kampion: You’ve always emphasized the importance of being a professional, and yet you admit to using marijuana and other psychotropic drugs. How does that work?

Nat Young: As far as I’m concerned, I learned a lot about professionalism by smoking dope. I never saw marijuana simply as fun, as something to fuck off with. I never placed any importance on it as something to use to get really stoned or fucked up. I mean, getting high, which is where I come from, was using the stuff as a contact drug. I use it simply as a method of making contact with the mediums that I’m using, which has been, ever since the 60s, either snow or water. I just really object to the fact that people think that you should smoke enough of it to fuck yourself up. I think that obscures the true potential of the drug.

I believe honestly that marijuana was a really important thing in my life; and brought me a great amount of understanding, and I don’t ever want to forget all those lessons that I learned in the late 60s and 70s… because I think those lessons have been some of the most significant in my life, and I still use them, whether I’m stoned or not. In other words, I’m saying that since the first time I was stoned, I’ve never not been stoned, or high. But now I might not smoke dope for a year. I mean, to me, “less is best.” Basically, I believe that with all drugs, the less you can use ’em the better—particularly ones that have such a marked influence on your whole well-being.

To me, it’s been a really significant ingredient in my life, but I think it would be a mistake to give the impression that any of the things that I got up to in surfing or any of the philosophies that I feel now are based on getting really fucked up. I mean, I try never to do that in my life. My whole life’s about tapping energy and riding waves and mountains, and, for what I do, I can’t afford to get fucked up. But I can make sure that my head is high, and this is something that every now and then is good to take—as long as you’re taking it to make a cleaner contact with the medium that you’re riding. It’s really simple, and I try to keep it simple.

I believe honestly that marijuana was a really important thing in my life; and brought me a great amount of understanding, and I don’t ever want to forget all those lessons that I learned in the late 60s and 70s… because I think those lessons have been some of the most significant in my life, and I still use them, whether I’m stoned or not.

DK: When did you first smoke pot? You’re going to be 60 this year…

NY: I first smoked pot on my first trip to Hawaii in the winter of 1962-63 with a couple of surfers, who are still good friends today.

DK: What was your first impression?

NY: Well, I was terrified then because I didn’t really know what it was, and my friends really couldn’t give me any understanding about it, so I only had one little puff. And certainly it had an effect, so much that I don’t think I smoked for several years after that—not until the mid-60s when we started to take psychedelics when we were playing with the whole shortboard thing… there was a lot of marijuana and a fair amount of psychedelics, and that, I think, was a very significant point. Actually, a lot of the places that we were getting to in surfboards around the world, particularly in Hawaii with Gerry Lopez, Reno Abellira, and Dick Brewer boards and in Australia with George Greenough, Bob McTavish, Ted Spencer, and myself and Wayne Lynch a bit later—this was certainly marijuana inspired.

Nat Young, the quintessential renaissance surfer.

DK: And that was in the country, well north of Sydney, right?

NY: Yes, we were all just over the border into southern Queensland—Noosa Heads all the way down to Byron Bay. I mean, there wasn’t too much that went on anywhere else. That area turned out to be one of the fine cultivating areas for pot in Australia because of the warm climate.

DK: In The History of Surfing you stated that you never smoked weed before a competition. How about free-surfing… do you get stoned before paddling out?

NY: Yes I do, especially if I am working with a new board of different design. I would say that for ten years of my life, when we were free-surfing, I never ever went in the water unless I was stoned. There was a period there, particularly when we were doing a lot of work on movies like Evolution with Paul Witzig and Morning of the Earth with Alby Falzon, when all of that was basically done using marijuana as a centring drug. But I now believe we were using it in excess—more than what was necessary to have reached that state. But I think the surfing that came out of that free-surfing was fantastic, and you only have to look at any of the movies or the stills that are available to understand that it was pretty groundbreaking stuff.

Just about everybody was indulging then—from the Biarritz area in France to the Californian coast and Hawaii, and on to the East Coast of Australia. I mean, those places were the high points of this development of surfing, and all of that can be attributed to a certain degree to marijuana intake.

I would say that for ten years of my life, when we were free-surfing, I never ever went in the water unless I was stoned.

But I think that when it comes to competition, it’s not even a part of it… and shouldn’t be. I tried it once and… I don’t think that it enhances your performance when you’re competing—all it does is, you become paranoid… especially when you’re there to win, and you don’t need anything to really confuse the issue at hand, which is to win a surfing contest. You certainly don’t need anything to give anybody else an edge, and I think it would because you become much more susceptible to thinking about what you’re doing and to having a talk to someone… and I don’t think that competition lends itself to that at all. Not if you want to win. It’s okay if you’re out there just to kind of fill in the blanks and have a nice time, but that was never my idea with competition. I was only there to win and then leave. I didn’t ever see it [competition] as a good thing; I saw it as a necessary thing.

I actually think that competition is a complete contradiction to what surfing represents, and I don’t think there should be any competition. I think that the whole thing is totally wrong, but that’s not the way the world’s set up. They’ve taken it and put it in this perspective, and we have to live with it. It still shits me!

Back in the mid-60s I was really focusing on winning. I had something that I was trying to achieve, and there was no room for that [pot] on that level. What I was trying to do was to win surfing contests and make a name for myself. So, I didn’t feel that pot was an ingredient that should be even remotely taken into account, especially when I found out what the properties of the drug were. But a bit later on, when I stopped competing—and by 1970, as you know, I pulled out of competition pretty much—and I was also living in Byron Bay, which as I said was very much an alternative community, and it was time to indulge for the improvement of my surfing. If you’ve seen Morning of the Earth, well, all of the surfing in that movie was done absolutely loaded to the gills.

Nat living an alternative community lifestyle in Byron Bay.

DK: So the time you did smoke pot before competing, that would have been back in the late 60s?

NY: Late 60s, Bells Beach. I remember it very well! [laughs]

DK: But not for the 1970 World Contest, though?

NY: Not literally while I was competing, but how long do the effects of marijuana actually last? From what I’ve read, it stays in your bloodstream for months, right? So it could very well be. But I mean, that was a classic example of the problem… because we were smoking so much dope in those days, we absolutely lost perspective on what the name of the game was. And the performance really suffered because we weren’t playing in the real world. We were playing in a world with perfect waves, which is fine when you’ve got perfect waves, but that doesn’t happen all the time. Y’know, usually in competition you don’t get good surf, what you get is sort of very ordinary waves, and what you have to do is make the most of the conditions, and there’s no way you can do that on a board that’s five-foot-ten long when you’re six-foot-one yourself. That was ridiculous! But, that’s why we lost, and rightly so. We deserved to lose. I mean, Rolf Aurness [the winner of the 1970 World Contest] was surfing the perfect piece of equipment for the conditions, and if you would have sat us down and sort of analyzed it before the competition, we would have been able to dig that in a second.

But probably our heads were clouded… and that’s a bit like what I’m saying about too much marijuana. We lost perspective on it. If I had been realistic about what I was trying to do down there in the varying conditions, there’s no way I would have had a five-foot-ten board as the only surfboard that I was surfing in the competition. And I say that in absolute honesty, in retrospect, which I suppose is very convenient, but then the reality of the situation is that we made the decisions and we lost the surfing contest based on that influence, which to my mind is just another example of excess… to actually have your perspective clouded. And that’s a very good example of it… that surfing contest.

I read this stuff every week that comes through my computer, and I just go, “My God! How can these people honestly think that that’s what surfing is?”

DK: A lot of pro surfers are hesitant to publicly state that they smoke weed for fear of reprisal by their sponsors, who for the most part smoke weed, too. What’s been your experience with this?

NY: Well, I feel that’s absolutely correct. But I think it’s much more subtle than that—the influence of the surfing organizations and the media are one of the gauges for sponsors making decisions, and, yes, I think it’s absolutely hypocritical. But there’s a lot of hypocrisy in the world, and that’s just another one of them. The problem is, we’re treated absolutely as a competitive sport, and that, as I said before, is a total misnomer in itself. I mean, I read this stuff every week that comes through my computer, and I just go, “My God! How can these people honestly think that that’s what surfing is?”

I mean, they’re the ones that surf every day, most of them, and yet they’ve got the audacity to think that it actually is a competitive sport, and not declare it what it really is. So it pisses me right off, but where does it start and stop? I mean, does it start with the ASP [Association of Surfing Professionals]? Does it go back to Quiksilver? I mean, give me a break! The whole thing is just a pain in the ass. It’s absolutely full of shit how they’ve painted surfing, and I really object particularly to where the ASP stands on the whole thing.

Nat, a skilled practitioner of gravitational gratification.

DK: The ASP has drug-testing policies now.

NY: I know, it’s just hilarious.

DK: Which is classic because there’s so much abuse of alcohol and other drugs by surfers, so it’s the usual discrimination about which high is allowed and which isn’t.

NY: And that’s just absolute bullshit! I mean, I just hate it so much, but I’ve also learned that that’s just the way it’s always gonna be. We fucked it up right at the start. Surfing should have never been considered to be as sport! I mean, nobody says about the performing arts or music or dance, like, we’re gonna drug-test. I mean, how dare they say that surfing is a sport?! I mean, I just think that it’s absolute shit. I don’t accept it, I don’t believe it, I don’t do it as a sport, and I don’t even think these people that make these decisions and surf every day do it as a sport. No way!

DK: Do you think that your understanding that surfing is more of an art form or at least a non-sport is something that came out of your marijuana experience? Would you have come to that realization without it?

NY: Well, that’s one of those retrospective questions. For me, I don’t think I can even assess that. I mean, Do I think that my outlook came from that? Yes, I think it probably had certainly an influence, because I think that when you have a drug that inspires you to turn more inward about your appreciation of… well, a lot of things in life.

But, I mean, personal experience with other people and the things you’re actually doing, that’s all good, and it’s a wonderful thing. But I think that you’ve also got to put it in perspective, y’know? And for me the correct perspective has been balance. Surfing did not ever qualify as a sport. With other normal sports, you have a net or a line, and it’s a very clear-cut thing, but I’ve never related to any contact sport being something I wanted to do, nor any sort of team activity other than the fact that you can learn how to play as a team. But when I learned how to play as a team, I learned that I didn’t never want to do that. So there’s so many sides to all of this and marijuana certainly had an effect on forming my life.

I’ll surf and ride mountains till the day I die because that’s what I like to do, and I think that’s what I was meant to do. That’s the essence of my life.

DK: It does get out of proportion.

NY: I think so. And I don’t know what the influence was, or where the actual influence stopped or started, or how I kind of got to where I got to here, I just know… I think that I’m more concerned with the people that didn’t appreciate this and didn’t experience this criticizing and putting a label on something which is not what the general participants in this activity feel is true.

DK: That’s a very good point. Right on.

NY: That’s what shits me about it. Here they are making these sorts of comments, all the way from the heads of all the organizations to the heads of the companies to a fuckin’ world surfing champion, and they’re all…! Anyway… in surfing or in snowboarding or skiing, the competitions are a relevant part of things, and it’s one way that performance levels are always being pushed. But if you were to let that be your reason for doing these activities, to my mind you’re really missing the boat. Because it’s not a competitive sport. It’s not even a competitive activity. It’s just simply something that you do—all of these activities—for your enjoyment. And I think that’s the perfect motivation for doing anything, which is for your personal enjoyment and personal development. I mean, I love it! I love it because I think carving is the essence of all of these games; that’s what the similarity is, and it’s good that we can even talk about this now because, as you know, I don’t have a problem with competition at all, but that doesn’t mean that it’s the be all and end all of what surfing represents. And I don’t think that they should have the right to put it in a box, and it really pisses me off with the sponsors. And I have no problem with telling any of ’em, and I’ve had this argument with the directors of Quiksilver, with all sorts of people. I mean, it’s not a problem for me, because basically I retired at 55, and I do projects that I like to do now, but I don’t do them for money anyhow. It’s a different system that I live under in Australia, and I get paid more money than I can almost spend every month, in the pension situation. I mean, I don’t need sponsors. They can take it and ram it up their ass. I mean, I’ll surf and ride mountains till the day I die because that’s what I like to do, and I think that’s what I was meant to do. That’s the essence of my life.

DK: Hey, do you have a funny story that comes to mind regarding surfing and pot?

NY: There are some hilarious ones, but to my mind one of the funniest is one of the simplest. I was taking off at Sunset Beach before one of the big contests in the late 60s. I can’t remember which contest it was, but I remember I was out there with a crowd of probably 50 other people in the line-up, and I caught this big wave at Sunset, and I was screamin’ down this wave, and I got to the bottom, and I just laid up a giant bottom turn (as you do at Sunset), and I’ve got the whole thing totally cocked and loaded when… a guy whispers in my ear! He’s obviously come from further back inside, and I didn’t see him at all—I was totally shocked, and, he whispers in my ear, he goes, “Hey, man, don’t bum my high!” That’s such a classic line! And I think I did bum his high. I didn’t mean to, but I think I did.

About the author:

Drew Kampion is a former editor of SURFER (1968-72), SURFING (1973-82), WIND SURF (1982-89), and WIND TRACKS (1996-99) magazines. He was Editorial Director for the Patagonia clothing company (1990-91) and Associate Editor for NEW AGE JOURNAL (1992). He founded, published, and edited the ISLAND INDEPENDENT (1993-96), an award-winning “bioregional magazine in newsprint,” serving the “maritime rainshadow” islands of Washington State. For his work with the INDEPENDENT, he received first prize for editing a periodical with a circulation under 50,000. Until recently, Drew was the American Editor of THE SURFER'S PATH, world’s first “green” surf magazine. His episodic parody, THE TEACHINGS OF DON REDONDO: A SURFER’S WAY OF KNOWLEDGE (as illustrated by artist Tom Threinen) was a regular feature of the magazine.

Drew is the author of THE BOOK OF WAVES (1989), THE ART OF CHRISTIAN RIESE LASSEN (1991), STOKED: A HISTORY OF SURF CULTURE (1997, revised 2003), THE WAY OF THE SURFER (2003), THE LOST COAST (2004), WAVES: FROM SURFING TO TSUNAMI (2005), DORA LIVES: THE AUTHORIZED STORY OF MIKI DORA (2005), and GREG NOLL: THE ART OF THE SURFBOARD (2007). He was also editor of THE STORMRIDER GUIDE: NORTH AMERICA (2002).

He is currently assisting Fernando Aguerre with his autobiography, SURF, SEX AND SANDALS: THE LATIN ART OF MIXING BUSINESS WITH PLEASURE and is at work on completing the story of Jack O’Neill, the inventor of the modern surfing wetsuit, JACK O’NEILL: IT’S ALWAYS SUMMER ON THE INSIDE.

Married with two children, Drew lives on an island in Washington State.

For more on Drew Kampion go to: drewkampion.com

-------

You may also like:

Surf Arising!

The youth will shine—the future of Jamaica's surf scene through the eyes of Billy Mystic

Surf Movie Tonight!

The Godlike, the Mediocre and the Hairy-Chested

Surf Jamaica

Weed, Waves & Rasta